Hypermobility in Sensitive Children

Understanding this overlooked aspect of your child's physiology can make all the difference in providing the right support.

If you liked reading this, feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack 🙏

My New Five-Week Course Starts Next Week!

There are still a few places left on my brand new five-week course:

Trust Your Instincts: Confident Parenting for Highly Sensitive, Strong-Willed Children.

If you’re raising a child who feels everything deeply and pushes back just as strongly, this course is for you. We’ll explore how to build connection, support nervous system regulation, and feel more grounded in your role — even on the most difficult days.

The first live 90-minute session begins on Friday 25th April 2025 at 12:30pm UK (BST) / 1:30pm Berlin (CEST) / 7:30am New York (EDT)

I’d love for you to join us — it’s going to be rich, grounded, and full of support.

What Previous Participants Are Saying:

“I can’t believe how deep Dr Genevieve’s work took us in only a few hours; it is transforming my perspective on myself and my daughter, and I feel so much more able to stay calm and access my love for her! I would whole-heartedly recommend it to anyone who wants to strengthen their ability to parent in a calm and connected way amid challenge and chaos.” — Kate, mum of a four-year-old.

Resonant Parenting Project #44

Over the past year, I’ve become increasingly curious about hypermobility, and I’ve been researching it in depth — because it seems to be a missing piece of the puzzle for so many of the children, teenagers, and adults I work with.

Much of what I’ve been learning has come through the generous insight and experience of my friend and colleague, Felicity Evans — a former teacher, Special Educational Needs Co-ordinator (SENCO), nutritionist and parenting coach, who’s spent decades supporting children at a grass-roots level. Her deep, practical knowledge of how hypermobility affects children in real life — not just in theory — has been eye-opening, and I’m incredibly grateful to her for introducing me to this way of seeing and supporting the body.

What Is Hypermobility?

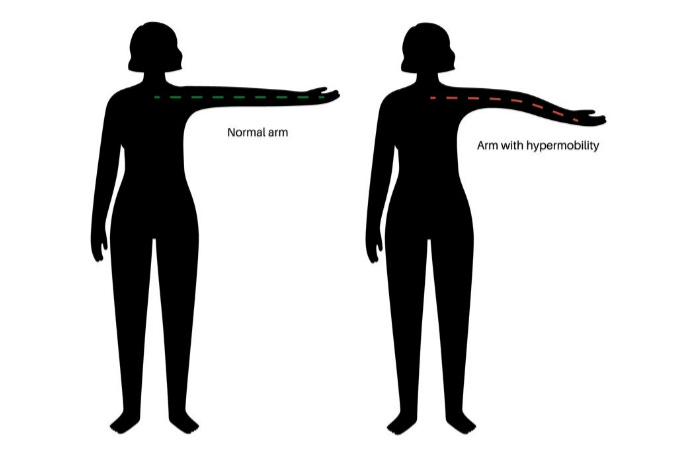

Hypermobility means a child’s joints move beyond the normal range — more easily and further than is typical. While it’s often linked with flexibility, it actually reflects a deeper difference in how their body is built.

The connective tissue (fascia) — the body’s internal “cling film” that wraps around muscles, joints and organs — is stretchier and less supportive than usual. As a result, the body can feel less stable and has to work harder to stay upright, coordinated and comfortable.

What the Research Shows

Hypermobility affects about a third of children and adolescents around the world, with a higher prevalence in girls, according to a review of studies published in 2020.

Hypermobility is genetic and tends to run in families. Research is showing clear associations between hypermobility and neurodivergence (which includes ADHD, Autism and Tourettes). A 2022 study by Dr Jessica Eccles, Associate Professor at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, found that neurodivergent individuals were twice as likely to be hypermobile compared to a control group.

While hypermobility can be an asset — most exceptional athletes, dancers and musicians are hypermobile (and looking back, I can see that my own hypermobility was probably linked to my talent for piano playing as a teenager) — it also can lead to challenges including joint pain, fatigue, anxiety and poor emotional regulation.

In a 2024 article in The Telegraph, psychiatrist and ADHD expert Dr James Kustow noted:

“A large cluster of people with hypermobility have wider health problems linked to the immune and autonomic nervous system.”

This suggests we’re not just talking about “bendy joints” — but a whole-body experience that affects how a person moves, feels and functions.

Debunking the Myths

While hypermobility can show up as extreme flexibility — bending thumbs to the wrist and folding legs behind the head, there are many assumptions about what it “should” look like.

The truth is, hypermobility comes in many forms, and it’s not always visible to the eye.

Many children who are hypermobile don’t appear obviously “flexible” at all. Instead, what we often see are children who:

Seem restless, distracted or “off-task”

Fidget constantly

Slouch or hunch over at their desks

Struggle to sit still and maintain focus

Avoid eye contact or withdraw

Difficulty with handwriting or fine motor tasks

Seek deep pressure (such as tight hugs, squishing into corners, or piling on cushions)

Seek extra sensory input (chewing, crashing into things, or constantly moving)

Seem to experience sudden waves of discomfort or overwhelm. They may might feel hot or cold, anxious, exhausted, or emotionally distressed without a clear trigger. These moments can be hard to explain and may look like zoning out, shutting down, or becoming tearful or panicky.

Complain of being tired, achy or uncomfortable

These aren’t signs of a “bad attitude” or “poor focus.” They’re signs of a body that may be chronically uncomfortable — a body doing its best to cope in an environment that doesn’t quite feel right. A body working overtime just to stay regulated.

It’s Not Just Joints — It’s Fascia

One of the most profound insights I’ve gained through conversations with Felicity is that hypermobility isn’t just about joints — it’s about fascia.

Fascia is the connective tissue that wraps around and supports every muscle, bone, nerve, and organ. It’s like an invisible web running through the body — playing a crucial role in postural stability, and nervous system regulation.

When the fascia is weak, underdeveloped or overstretched — possibly influenced by factors such as genetics, preconception health, pregnancy, birth and early developmental patterns (e.g., a weak diaphragm, or underused core muscles) — the body becomes less stable. And this instability — this lack of inner scaffolding — might contribute to what we observe as hypermobility.

As Felicity says:

“Hypermobility is a condition that affects a child 24 hours a day. The body is working overtime to hold itself together, and this can lead to emotional overwhelm, delayed milestones, and behaviours that are often misunderstood as ‘disruption’ or ‘disinterest’.”

A child with weak fascia may not feel “held” from the inside. Their body doesn’t offer the firmness or feedback it needs to feel safe, organised and emotionally regulated.

So they compensate — by fidgeting, withdrawing, slouching, or seeking strong physical input that helps their body feel more together.

A Body Doing Its Best

These children aren’t choosing to be disruptive or inattentive — they’re doing their best to manage a body that doesn’t always feel ‘held together’, safe or supported.

When we understand this, everything changes.

We move from asking:

“What’s wrong with this child?”

to:

What’s going on inside this child’s body — and how I can help them feel more at ease?

How Can We Support Children With Hypermobility?

Children with hypermobility can thrive — but they need informed, attuned support from both health and education systems. And they need adults who truly see them.

Over the coming months, I’ll be exploring some of the many ways we can support hypermobile children — both practically and relationally.

Possibilities include:

Primitive reflex integration1

Supporting core strength

Supportive language and tone to create a sense of “internal holding”

Helping children (and parents) self-regulate with deep breathing practices and encouraging nasal breathing

Sensory tools to help children feel more settled and connected in their bodies

Nutrition to support mood, energy, and connective tissue health

Advocating in schools and working with teachers and SENCOs to get the right support in place

Seeing the Whole Child

I’m so keen that we don’t rush to label or pathologise our children — but that we continue to look deeper, with curiosity, compassion and a willingness to listen. Because hypermobility doesn’t just come with challenges. It also comes with many beautiful gifts: creativity, sensitivity, empathy, deep perception, and a wisdom beyond their years.

Our children’s bodies are telling us so much.

We just have to learn how to hear them.

I’m very much at the beginning of this journey. I certainly don’t have all the answers, but I have many walking questions. I’m looking forward to sharing more as I learn, and continuing this conversation with those of you who are walking alongside me.

And with deep gratitude to Felicity Evans for her wisdom, experience and the powerful work she continues to do with children and families every day.

I write the Resonant Parenting Project in between my work as a clinical psychologist, conscious parenting coach and looking after my seven-year-old daughter Matilda. Any support from readers through liking, sharing, subscribing or buying me a coffee helps make this work sustainable. Thank you!

I highly recommend neuro-developmental therapist Lucy Simmond’s work on primitive reflexes.

I also highly recommend the work of physiotherapist Suzy Bentley-White.

I see a lot of this in my clinical practice with gifted and neurodivergent folks. Thank you for raising awareness about this, along with what helps.

Thank you Genevieve for this very important newsletter. In my practice as a primitve reflex therapist, I see increasing numbers of children who are hypermobile. If we can recognise the signs and implications of hypermobility, we will be better able to understand and support many of today's children.